Seton Monday: Art from More Beautiful and Amazing 2

Seton Monday is a bi-weekly blog series sharing updates and learnings on Ernest Thompson Seton and the Academy’s Seton Legacy Project, curated by David Witt. In this edition, David shares art from the Seton Legacy Project’s 2019 art exhibition More Beautiful and Amazing.

Learn more about the 2020 exhibition at

http://ernestthompsonseton.com/

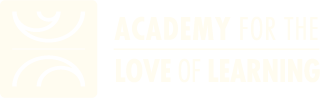

Matt Celeskey Animals of the Past

Featured image: Matt Celeskey, It is only a question of time, Mixed media/2019

I feel a sense of wonder and awe at our destruction of the other creatures of this world. Both for those beings already gone and those on their way out. Do we believe that the horror of this will be less if we manage to look away and pretend not to see? But what happens when visual artists refuse to let us off so easily? The dead and the passing deserve our recognition. Seton suggested that if we cannot bring ourselves to save the others for their sake, we should certainly save them for our own sake. He didn’t think we could manage without the presence of our co-travelers on this planet. Even if we could, would we really want to?

MATT CELESKEY AS PALEOARTIST

As a ‘paleoartist,’ most of my work involves the reconstruction of species that lived long before there were any humans. From an imperfect record of fossil bones and other petrified impressions, I try to imagine plausible scenes in order forge and share connections between the viewer and long-extinct organisms. Although much about these ancient organisms is unknown and unknowable, we can find unmistakable ties of kinship and experience connecting us across millions of years.

The four species bordering this piece–the Great Auk, the Bluebuck, Steller’s Sea Cow and the Dodo–are only separated from us by a few centuries. To imagine them alive, there is a comparative wealth of data to work from. We have not only their bones and skins, but also mummified or taxidermied specimens preserved in museum collections. We also have the written and illustrated records of men who saw these animals, and heard them, and in some cases smelled and tasted them before the last of their respective kinds disappeared from the earth.

But all the specimens and data and records are, at best, a pale reflection of a living species, and these animals are as lost to us today as any tyrannosaur or trilobite. In some ways, these recent losses cut more deeply–we have a greater sense of what we have missed, and we cannot avoid the fact that our own species is responsible for their death. Seton worried that the jaguar would be headed to the same fate. A century later, there remains a small window of hope that the jaguar’s historic range might be restored, but in that time the ghosts of countless species loom even larger over the wild things that remain at the edges of our world.

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON AND THE JAGUAR APOCALYPSE

Man is, of course, the implacable enemy of the Jaguar. It is only a question of time now, and maybe very little time, so far as the United States is concerned, before man sends this masterpiece of creation the way of the Dodo, the Auk, the Antelope, and the Sea-cow. (Lives of Game Animals, Vol. I, pg. 31, 1925)

As a historian I have spent a good deal of time speculating on this: If you don’t know where you came from, how can you know where you are going? When Seton came to New Mexico in 1893 he observed the cowboy life in all its rough edges. You had to be tough to survive in that environment. Even as he lived it, Seton closely identified with the romance of the West; it never lost his hold on him. Neither has its lost its hold on those of us who live here now. But to depict it—the current reality and the nostalgic past—who better to show to us than someone who has lived (and still lives) the ranch life of the West? Keith Walters’ work demonstrates that strong authenticity. See this work and the others in the Seton Gallery 2019-2020 exhibition at the Academy for the Love of Learning.

KEITH WALTERS AND THE HISTORIC WEST

I am an artist and sculptor from Cimarron, New Mexico. I grew up in Springer, NM and graduated Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. I spent 10 years cowboying on ranches in New Mexico, Nevada, and Wyoming, before embarking on a 30-year career as a prop master in the film business. My artwork typically reflects my love for the American West, its history, people, and animals. This particular piece is a pen and ink drawing done as an illustration for Max Evans’ book ANIMAL STORIES. It depicts a moment in the struggle for survival between a young mare and a mountain lion.

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON AND THE COUGAR

Of all the beasts that roam America’s woods, the Cougar is the big-game hunter without a peer. Built with the maximum power, speed, and endurance that can be jammed into his 150 pounds of lithe and splendid beast-hood, his daily routine is a march of stirring athletic events that not another creature—in in America, at least, can hope to equal. (Lives of Game Animals, Vol. I, pg. 95, 1925)

Karen Ahlgren’s mammals and birds appear to have sat (or perched) to have their portraits done. They often show startlingly bright fur or feathers, and in the case of this wolf may compellingly stare out at the viewer as if they want something from us. Maybe respect. Many of us want something from them—a sense of wildness. Even if you don’t have ready access to wolves-in-the-wild, you can visit a wolf sanctuary to experience wolf magnificence.

KAREN AHLGREN AND HER ANIMAL PORTRAITS

At an early age I soon realized that animals were often viewed by humans as something to ‘own’, use, hunt or consume. I became a champion of these beings recognizing their need for a voice in our world. I was working in the film industry for many years when I decided to leap into the abyss and acknowledge their existence, sentience and beauty in the only way I knew how- to paint them.

Using a non-local color palette pleased MY muse and I was pleasantly surprised when these portraits were enthusiastically received.

May we all develop respect for ALL animals living on this planet and recognize their importance for balance and yes, their inherent right to live their wild lives.

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON VIEW OF WOLVES

Thus I have offered evidence of the courage, the chivalry, the strength, the playfulness, the love loyalty, the fidelity, the friendliness, the kindliness, the heroism, the goodness of the Wolf—completing my attempt to set before you the faithful and fearless portrait of a creature so long maligned; to piece together the little scraps of truth I have found in countless hunter-tales, like gold raked out of garbage bins; to make known the wild one’s true character and his way of life as it really is. Now, with the evidence before me and much more of the same available, and with the story of Lobo in mind (for it is true in the main), can any one wonder that I love the Gray-wolf and credit him with true nobility of character—with the attributes of a splendid animal hero?” (Lives of Game Animals, Vol. 1, pg. 337, 1925)

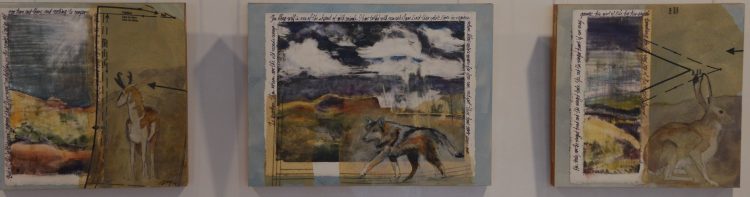

Amy Flowers Ecological Relationships

The way of the wild is restless. Seton’s animal stories present a word portrait of the individual characters making their challenges and triumphs a matter of deep emotional involvement for the reader. One rabbit may look much like the next, but to take one example, the experiences of “Raggylug” in Wild Animals I Have Known, while common to rabbit-kind, are also his alone. His mother, Molly, teaches him the foot thump code known to all rabbits, but their ability to avoid foxes and dogs comes both from instinct and the experience of individual learning. Those who chase and for those who are chased are both individuals and joined units in forever interdependence. The three panels of this work by Amy Flowers shows this relationship—the three images are separate but connected as part of a larger mosaic.

AMY FLOWERS AND WILDLIFE

Born an artist, I am self-taught with the privilege of having several gifted mentors throughout my artistic career. Primarily a painter, I began working with watercolor in my teenage years. Early work was created in a traditional, realist style using pastel, charcoal, pen and ink and moving into watercolor. About 20 years ago I began experimenting with alternative art media; this experimentation led to the use of acrylic paint, inks, collage and the development of a more abstract vision.

My work is energetic and vibrant, and I paint using multiple thin layers of acrylic to achieve the glow and depth that my pieces are known for. Acrylic is worked under and over the collage elements, fusing the paint with objects and ephemera. Inspired by natural color, form and the little details that surround us, I paint to express the energy and joy I find in everyday adventures and environments.

“Eat, Prey, Love” was created as a response not only to the process and influence of Seton and his work on my own studio practice, but as a contemporary reaction to what we have lost in the modern world. I grew up reading about the era of abundance in North America, imagining the Great Plains dark with herds of buffalo as far as the eye could see, landscapes raw and unsullied by the approaching Industrial Age. I memorized images recorded and painted by early artists and explorers of the West while filling up my own sketchbooks, drawing and painting, pretending to be the grand explorer in my own little patch of backyard woods. The thrill of spotting any wildlife was considered a privilege, a lucky find—unlike the history I was reading about. “Eat, Prey, Love” reflects that same thrill I had as a kid, seeing that one solitary animal in the wild, while realizing it shouldn’t be the only creature left standing in the landscape.

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON AND THE TRAGIC END FOR ANIMALS

For the wild animal there is no such thing as a gentle decline in peaceful old age. Its life is spent at the front, in line of battle, and as soon as its powers begin to wane in the least, its enemies become too strong for it; it falls. There is only one way to make an animal’s history un-tragic, and that is to stop before the last chapter. (Lives of the Hunted, pg. 10, 1901)